Los Angeles Ghost Town

Have you ever flown out of LAX and saw what appeared to be an abandoned city below? What is it? Los Angeles Ghost Town?

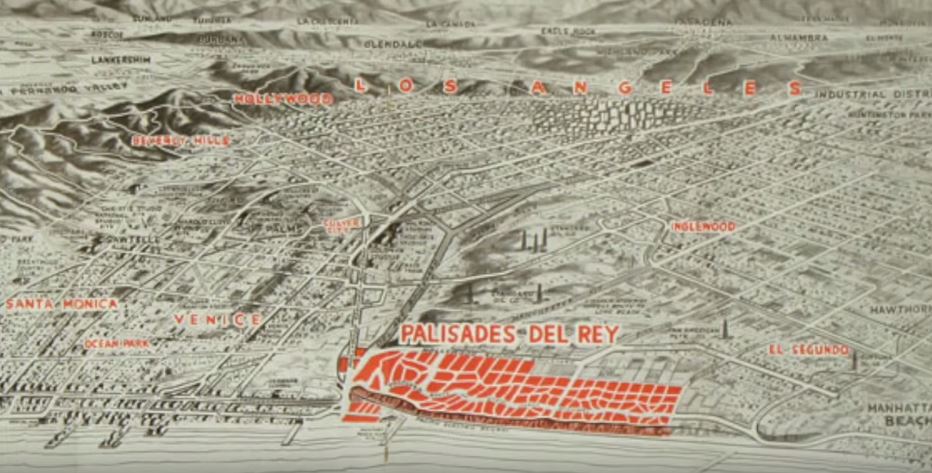

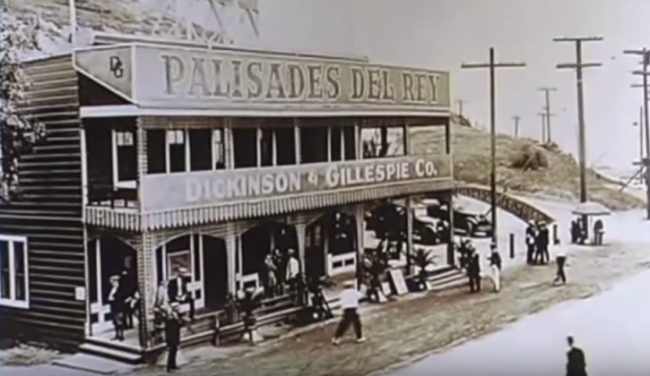

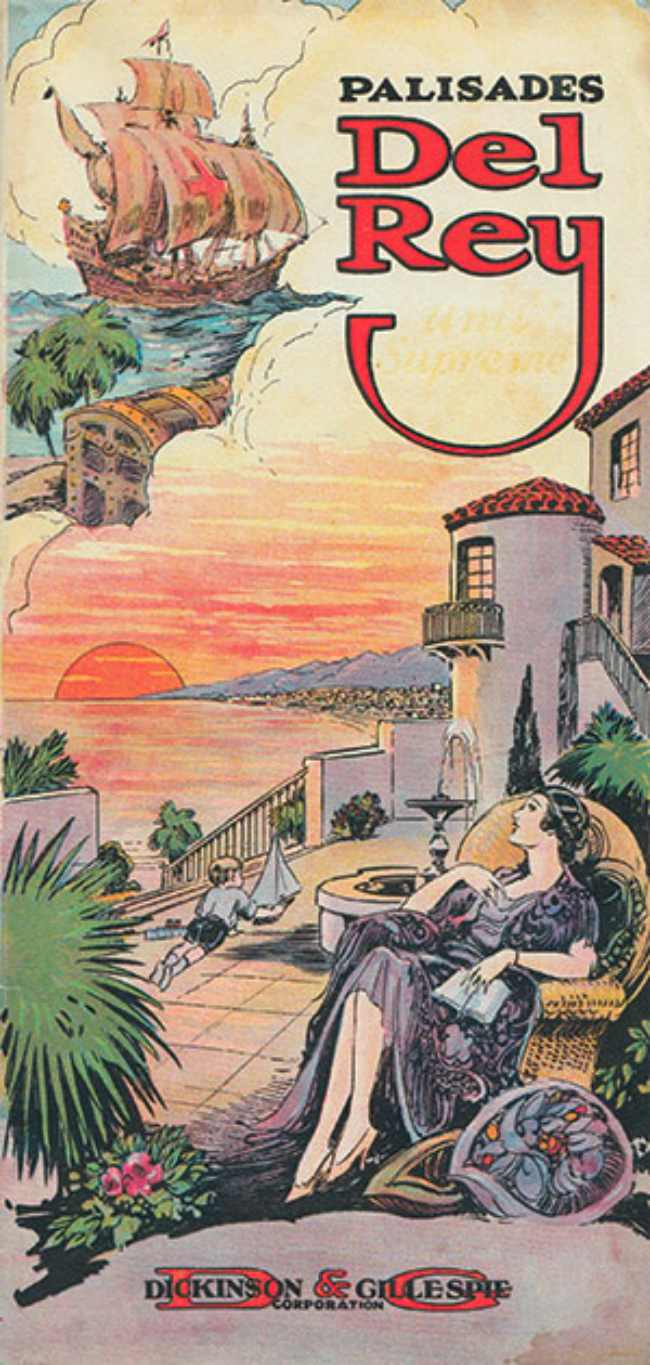

Well… Yes. Today it is a ghost town. Palisades del Rey (aka Surfridge) was a beachfront city developed in the early 1920’s by the famed Dickinson & Gillespie Co.

At the turn of the century, Playa Del Rey (known then as Palisades Del Rey) was aptly named King’s Beach. In Spanish, Playa Del Rey stands for “Beach of the King” or “King’s beach”.

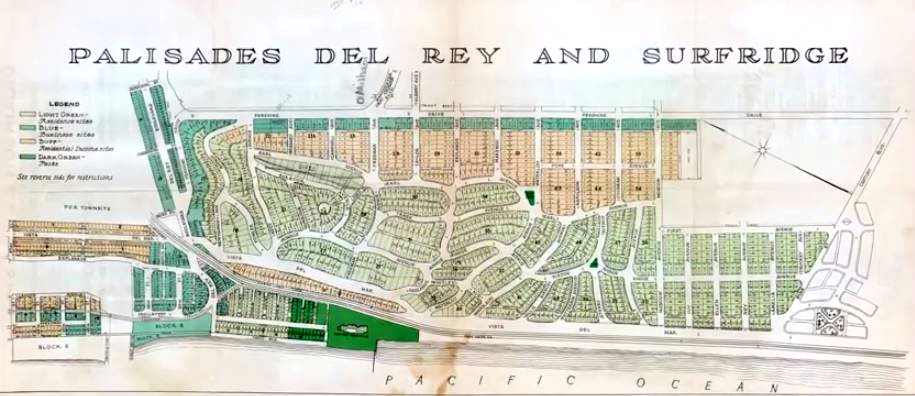

Palisades del Rey was the name of the original 1921 neighborhood land development by Dickinson & Gillespie Co. that later came to be called Playa del Rey.

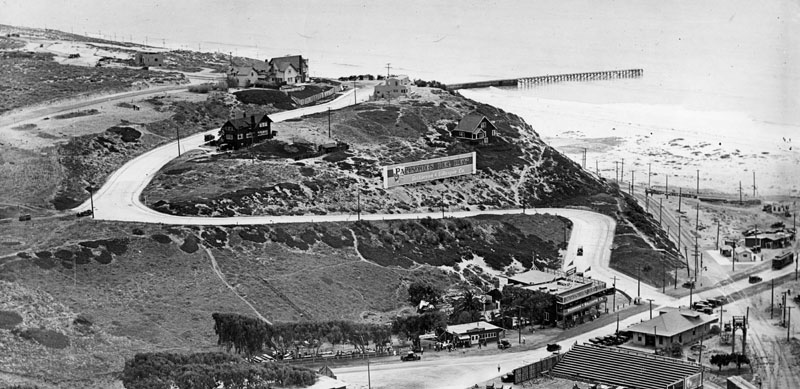

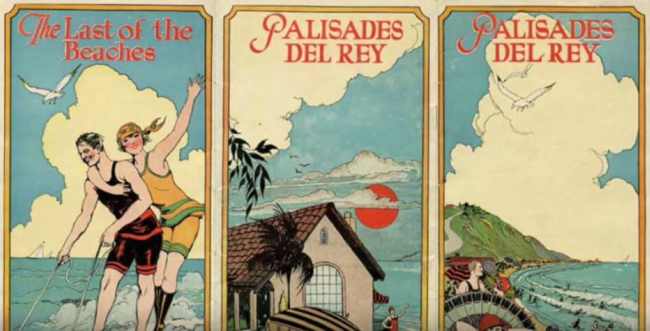

A beautiful coastline, oil-rich soil and miles of unspoiled dunes made it a destination for real estate developers, oil diggers and tourists.

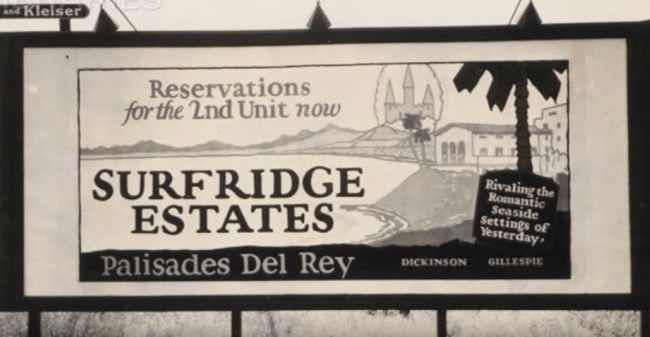

In 1921, the firm Dickinson & Gillespie purchased a three-mile stretch they would develop into Palisades Del Rey, Surfridge Estates, Del Rey Hills and Surfridge. All in the district of Los Angeles County, California and under the direction of Fritz Burns. (He also later developed Olympic Beach.)

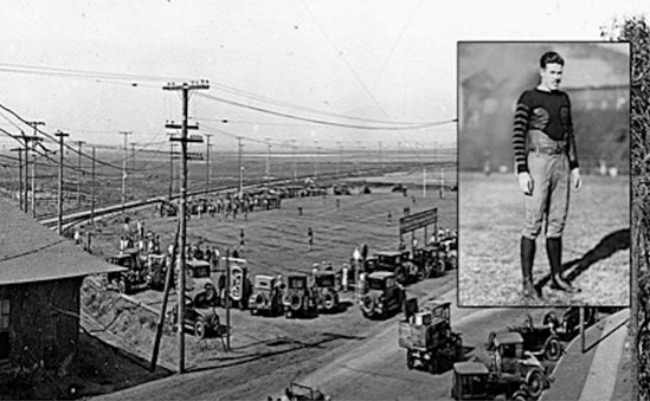

Fritz regularly bragged that he would be a millionaire by age 30. Part-politician, part-P.T. Barnum, all salesman, he actually achieved that goal, thanks to his real estate investments, his pioneering professional football team, the Los Angeles Buccaneers, and his command of the sales force that subdivided and sold the lots in Playa Del Rey.

(More on Fritz and football.)

The area was beautiful and conveniently located, and the hills…

The rolling hills are the result of ancient, wind-blown, compacted sand dunes which rise up to 125 feet above sea level originally called and often referred to as The Del Rey Hills or “The Bluffs”.

These dunes run parallel to the coast line, from Playa del Rey, all the way south to Palos Verdes. It lay at an elevation of 135 feet (41 m).

The perfect vista point and high above the water for exclusive oceanside living.

Real estate developer Fritz Burns, a mastermind behind the project imported palm trees to flank the entrance. He put up his signs and businesses started booming.

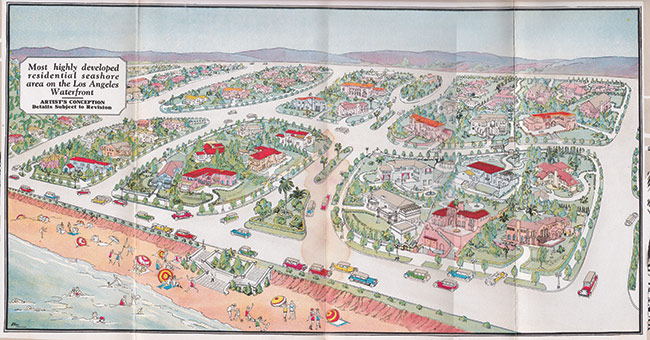

It was an easy sell; the rich and famous flocked to Surfridge for a piece of paradise.

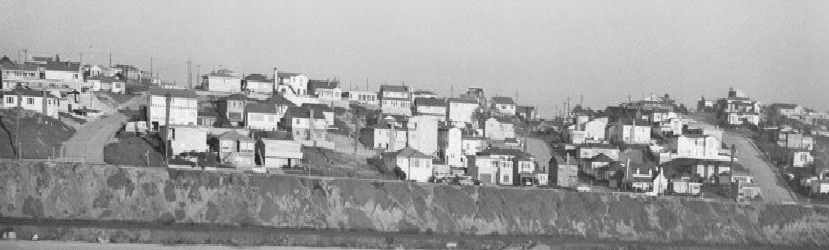

And they began to build cottages, houses and even mansions on the beach.

The seclusion of the developments appealed to actors and directors and all of the houses in this area were custom built.

Many of the beach homes owned by Hollywood stars, actors and producers.

Hollywood royalty that invested in the area included William de Mille, Cecil B. DeMille, Charles Bickford and Mel Blanc and others.

In the early days, actress Mae Murray built a custom-built, enormous, ocean front property at 64th Street & Ocean Front Walk in Playa del Rey (a stretch of coastal land near today’s LAX airport).

This is where she held lavish parties that lasted for days.

A southern portion of Playa del Rey became known as Surfridge.

Decades before celebrities were spotted on the bluffs of Malibu, stars of the silver screen took retreat in the dunes above Dockweiler.

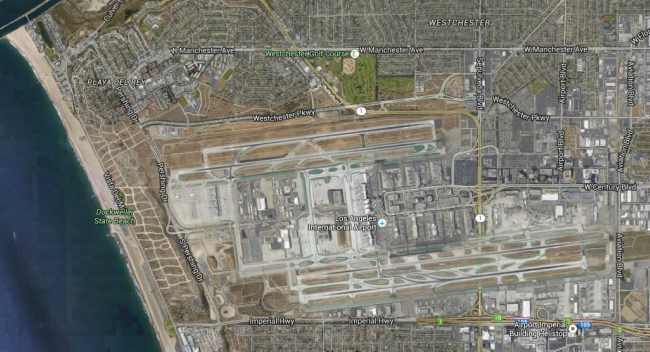

A neighboring area east of this playground was also attracting the spotlight. Mines Field, a 640-acre parcel of farmland, had become a venue for people to enjoy air races and shows that were popular in the ‘20s and ‘30s.

A small airfield opened to the east of Surfridge in 1928.

It became a popular location for residents to see air shows. These events drew large crowds.

Along with participants Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart, attendees included Marion Davies, Will Rogers, Bill Boeing and Donald Douglas. It was an exciting moment in 1928 when the Los Angeles City Council selected Mines Field as the site of a new airport for the city, and the farmland was transformed into dirt landing strips.

Surfridge was developed in the 1920s and 1930s as “an isolated playground for the wealthy.” In 1925 the developer held a contest to name the neighborhood and awarded the $1,000 prize to an Angeleno who submitted “Surfridge.”

The Los Angeles Times wrote that Surfridge was chosen “due to its brevity, euphony, ease of pronunciation … but above all because it tells the story of this new wonder city.”

Salesmen pitched tents on the sand dunes and sold lots for $50 down and 36 monthly payments of $20. House exteriors could only be stucco, brick or stone; frame structures were prohibited.

Development was slowed by the onset of the Great Depression, but in the early 1930s the wealthy began to buy lots to build large homes.

Surfridge flourished from the late ‘30s through the late ‘50s. Dickinson & Gillespie suffered as a result of the Great Depression and sold their interests to the bank.

Fritz Burns lost his own mansion and lived in a tent on the beach until he rebuilt his fortune.

The growing number of commercial flights into Los Angeles following after World War II meant a higher number of planes flying low over Surfridge.

Many residents learned to coexist with the noise from propeller planes, but jet engines were impossible to ignore.

“If you lived in Surfridge prior to the late 1950s, you had to raise your voice a bit when having a conversation.

After the jets came, you had to literally stop talking when they took off,” said Duke Dukesherer, a business executive who has written about Surfridge’s history.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the area was condemned and acquired by the City of Los Angeles in a series of eminent domain purchases to facilitate airport expansion and to address concerns about noise from jet airplanes. Homes were sold, and some went to auction.

All homeowners were forced to sell their property to the City and soon, it was all but abandoned.

Several homeowners sued the City and remained in their houses for several years after the majority of houses were vacated.

But it was not pleasant.

Eventually all the houses were either moved or demolished.

Some of the streets are still here. Maybe you remember the names? Rindge, Jacqueline, Kilgore? But sadly, no cars have passed over them in over 25+ years. The cement is cracking and no one is even allowed to walk them.

Knee-high weeds breach the asphalt, running in lines like lane strips and foundations still stick out of the ground.

A few old, globeless lampposts are the last standing pieces of a beachfront community wiped from the map.

Reminding us of a time past…

Today, every home is gone, nearly 800 razed to nothing but a few low retaining walls.

Ging there, you see only barbed-wire fences protecting vacant land and old streets where houses once sat and lives were once lived.

A once thriving, populated and vibrant beach colony is now only a ghost town, a fading memory. Most people in L.A. have no idea it ever even existed.

Broken streets, a park and a butterfly preserve are all that remain of a neighborhood that once stood under the flight paths of LAX take-offs. The area is now the protected habitat for the endangered El Segundo blue butterfly.

And speaking of the butterfly…

El Segundo blue is a federally designated endangered species butterfly local to a small dune ecosystem in Southern California that used to be a community called Palisades del Rey, close to the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX).

In 1986, the airport created the Dunes Restoration Plan to return the dunes to their original occupants, the El Segundo Blue Butterfly—the first insect designated as an endangered species in 1973. The butterflies survive on coastal buckwheat that grows on 200 of the 300 acres of the remaining undeveloped land adjacent to the airport.

The El Segundo Blue Butterfly Habitat Preserve next to LAX exists to protect the species.

There are only three extant colonies of this tiny butterfly still in existence. The largest of these is on the grounds of LAX; a further colony exists on a site within the huge Chevron El Segundo oil refinery complex, and the smallest colony is an area of only a few square yards on a local beach.

The main threat the Blue Butterfly faces is the destruction to its habitat. This is caused by the urbanization and industrialization of the LAX and the company Chevron for removing the butterfly’s host plant, buckwheat.

But back to the neighborhood…

In the screenshots below, you can see the neighborhood streets, and where the airport is in relation.

I have to admit, I wouldn’t want to live there now.

In the front of the abandoned cities is Dockweiler State Beach. It’s has 3.75 miles (6.04 km) of shoreline and a hang gliding training area. Although a unit of the California state park system, it is managed by the Los Angeles County Department of Beaches and Harbors.

You can also camp there as it has an RV Park as well.

Dockweiler State Beach RV Park. It is described this way on Wikipedia:

“Dockweiler State Beach is in the Playa del Rey neighborhood at the western terminus of Imperial Highway. Between the beach and the airport lies the ghost town of Palisades del Rey.”

The park also boasts the Dockweiler Beach Hang Glider Flight Training Park, where beginners can learn the sport of hang gliding. Students launch off 25-foot-high (7.6 m) dunes. The facility was built by the city and county and is operated by concession WindSports.

Literary Mention: There’s a weird/sexy encounter in an abandoned Surfridge house in Thomas Pynchon’s LA-at-the-end-of-the-’60s novel Inherent Vice but other than that and the strange abandoned roads you see as you take off from LAX, just a few photographs and postcards remain,